NAP Expo 2019: Raising adaptation Ambition by Advancing National Adaptation Plans

4 to 8 April 2019, Songdo, Republic of Korea

Daily Update, 11 April 2019

On the fourth day of the NAP Expo, a country platform session put a spotlight to the countries that have submitted NAPs, providing a space to communicate the countries’ key vulnerabilities, needs, priorities and adaptation actions. It gave an opportunity for countries to present their NAPs to other country delegates and representatives of relevant organizations and agencies that are supporting the process of formulation and implementation of NAPs.

A global youth adaptation dialogue kickstarted today, strongly signaling that the youth are eager to be involved in the process.

Methodologies to enhance adaptation planning and implementation such as use of Google Earth Engine for NAP data needs; digital agriculture and vulnerability modelling in the coastal areas using hyrdo-dynamic modeling were explored throughout the day.

The Regional Technical Expert Meeting for Adaptation (TEM-A) led by the Green Climate Fund was also held in parallel along other sessions such as LIFE AR of the LDC Group.

Presentation of National Adaptation Plans by the least developed countries

Presentation of National Adaptation Plans by the least developed countries

Country platform – Presentation of National Adaptation Plans

As at April 2019, thirteen developing countries have submitted their NAPs to the UNFCCC Secretariat, four of which are least developed countries. At the country platform session, these 4 countries – Burkina Faso, Ethiopia, Sudan and Togo were given the spotlight to present their key vulnerabilities, needs and adaptation actions as identified in their National Adaptation Plans. While the Republic of Kiribati has not submitted a NAP yet, a different approach to how it developed its NAP, which is integrated in the disaster risk reduction and management plan, was presented conveying the message that the NAP can build on existing strategies and plans.

Key challenges and difficulties that are commonly encountered by these countries in developing their NAPs include multi-stakeholder consultation, availability and accessibility of data, seamless coordination across government and ensuring buy in of all ministries and actors in the government. With regard to implementation, a common challenge is securing funding for implementation of the policies, programmes and projects identified in the NAP.

While funding constraints continue to face these LDCs in implementing their adaptation actions, new opportunities such as engagement of private sector and other non-state actors have strongly emerged and should be tapped for implementation.

What strongly emerged from the discussion is the importance of NAPs as the central vehicle for planning and implementing climate change activities. It is therefore important for countries to understand at the onset that the NAP serves as a platform for coordinating adaptation efforts.

A main takeaway of the session is the affirmation that submitting a NAP does not mean countries have already adapted. It is vital for adaptation as it serves as the starting point to properly lay down concerted actions for adapting to climate change in the medium to long term.

Global Youth Adaptation Dialogue: Capturing the voice of young people

Across the globe, youth have been stepping up to develop and deliver innovative adaptation projects and initiatives. As visionaries and budding leaders, these young people have taken an active role in driving forward climate action by developing practical solutions to climate change impacts at the local, national and international level. In a South – South dialogue held at the NAP Expo, young people from Malawi and Korea exchanged experiences in engaging in climate actions in their countries.

Participants and organizers of the Global Youth Adaptation Dialogue at the NAP Expo 2019. The Dialogue was moderated by Mr. Emmanuel Dumisani Dlamini (center), Chair of the UNFCCC Subsidiary Body on Implementation.

Participants and organizers of the Global Youth Adaptation Dialogue at the NAP Expo 2019. The Dialogue was moderated by Mr. Emmanuel Dumisani Dlamini (center), Chair of the UNFCCC Subsidiary Body on Implementation.

In Malawi, Lakeshore Agro Processors Enterprise, a leading youth-owned agribusiness in Malawi, collaborates with local farmers, university students, and the Ministry of Agriculture in Malawi, to promote climate resilient farming practices. The company builds the capacity of young farmers and women engaged in the business as partners, not beneficiaries. It offers an innovative package of microfinance services to youth groups through innovations that include group lending, peer monitoring and joint liability for climate change adaptation.

In Korea, there is a budding movement of young people who are engaging in climate action. Green Environment Youth Korea (GEYK), a youth platform in South Korea was established to share knowledge and experiences and to catalyze sustainable behaviour change within communities. At the heart of this platform are energetic and committed university students who believe that cross generational cooperation is essential to address the climate crisis. Sustainable Development Solutions Network (SDSN) Youth was created to empower youth globally and create pathways for achieving the SDGs. Research findings showing that, while young people are gaining awareness and understanding of climate change, this knowledge is not personalized. To keep climate change high on the agenda and stimulate progress on climate action, the Korean government offers training opportunities, such as the International Expert Training Course through the Ministry of Environment.

Availability and access to funding is a formidable challenge for youth-led initiatives. Most funding is directed to government structures who often do not put in place clear processes or guidelines for engaging the youth. This is a missed opportunity to channel the insights and strengths youth bring to the table into transformational and far reaching climate action.

Integration of agriculture sectors in NAPs

The Integrative Framework for National Adaptation Plans and Sustainable Development Goals – the NAP-SDG iFrame by the UNFCCC LDC Expert Group (LEG) primarily takes into account the intrinsic links between adaptation and the achievement of the SDGs. It helps in identifying risks and vulnerabilities as part of a whole system of interests and helpful in addressing the coherence and synergy of adaptation action at multiple scales and levels, including over time, considering other relevant frameworks such as the SDGs and the Sendai Framework for Disaster Risk Reduction 2015–2030 (UNFCCC, 2018).

Figure 1. Systems approach diagram on forestry, tress and agroforestry

Figure 1. Systems approach diagram on forestry, tress and agroforestry

The Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) of the United Nations is attempting to apply the systems approach, following the NAP-SDG iFrame, as a framing to the new supplementary materials to the NAP technical guidelines focusing on the integration of forestry in NAPs, leveraging its potential for transformational change.

Country cases from Vietnam, Thailand and Uganda were highlighted showcasing how the close linkages and interaction of the agricultural systems were considered in the Agriculture NAPs. A closer look on the current NAPs submitted to the UNFCCC secretariat revealed that although forests and trees features well in them, it does not provide concrete actions as to how it plays an adaptation role. There is therefore a need to organize a forestry focused adaptation reflection and a dialogue between forestry and other sectors so that the forestry sector can integrate in its management plans additional objectives and communicate in return what is needed to make it possible.

Methodologies to enhance adaptation planning and implementation

Digital agriculture to leapfrog adaptation pathways

Digital agriculture encompasses an array of technologies, channels, and analytic capabilities that are applied to make farming more precise, productive, and profitable. Digitization of farming systems, based on true interactivity with farmers over digital channels, is becoming critical for adaptation to climate change. Big data, generated in the pursuit of farming intensification on individual farms, can enable analyses on a larger scale that can inform adaptation planning across landscapes or regions. On the session of the CGIAR Research Programme on Climate Change in Agriculture and Food Security, speakers showcased existing and emerging digital solutions that will change the game for adaptation in agriculture. It also identified areas under the elements of the process to formulate and implement NAPs to which strategic role of digital agriculture could potentially benefit. Digital tools are becoming a new form of capital that will allow us to move faster towards transformation for achieving SDGs.

Vulnerability modelling in coastal areas

Modelling coastal vulnerabilities require looking both at inland and coastal processes to connect land-based drivers of vulnerability to coastal modelling. In doing so, the result can enhance climate change adaptation outcomes in the coastal area.

Hydrodynamic modelling can be used as a decision making tool in formulating policies on risk mitigation and adaptation of floods under differing climate and/or engineering scenarios in project areas. Example application in Jakarta, Indonesia used the model for flood reduction and climate resilient infrastructure development pathways to better assess the flood risk in the coastal areas.

Figure 2. The Coastal Hazard Wheel 3.0 consisting of six coastal classification circles, five hazard circles and the coastal classification codes. It is used by starting in the wheel centre moving outwards through the coastal classification (modified from Rosendahl Appelquist and Halsnæs 2015 and Rosendahl Appelquist 2013)

Figure 2. The Coastal Hazard Wheel 3.0 consisting of six coastal classification circles, five hazard circles and the coastal classification codes. It is used by starting in the wheel centre moving outwards through the coastal classification (modified from Rosendahl Appelquist and Halsnæs 2015 and Rosendahl Appelquist 2013)

Coastal Hazard Wheel, an open access initiative, is a universal coastal management framework that can be used for multi-hazard-assessments at local, regional and national level, and identification of hazard management options for a specific coastline. It also has a standardized coastal language to communicate coastal information and aims to boost climate change adaptation and bridge the gap between scientists, policy-makers and the general public.

Google Earth Engine NAP Data Catalogue

The application of Google Earth Engine to Open NAPs was first explored in NAP Expo 2018. This cloud-based platform for geospatial analysis brings the power of geographic information systems (GIS) and remote sensing at scales up to the global level. The potential to apply this tool in Open NAPs and eventually in NAPs in different countries without the need to invest heavily in GIS and RS processing infrastructure proves to be an easy and obvious solution. This year’s NAP Expo, participants attempted to identify what NAP data needs, going beyond the climate information datasets, that support the formulation and implementation of NAPs can be mapped using this technology and work towards a development of a NAP Data catalog, building on readily available information as well as new and emerging datasets produced by countries and researchers that are not so readily available to the adaptation community. The intention is not to create another data pool but to be able to map to existing data sources, knowing where to access it and possibly integrate AI models and approaches that would best suit the requirements. The group agreed to launch this as an ongoing collaboration and an online sign up form was made available for interested individuals.

Subnational adaptation

Enabling planning and financing at the local level – learning from the experience of Cambodia, Korea and Mozambique – is a way of accelerating the delivery of NAPs.

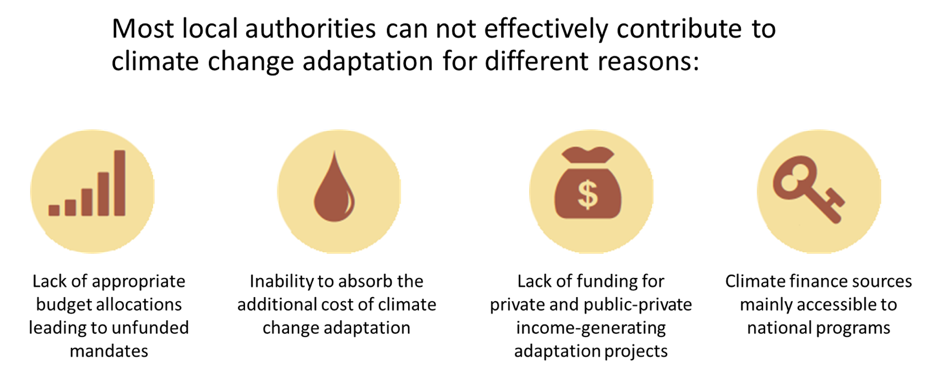

Local authorities are in a unique position to identify and implement the responses that best meet local needs. Typically, they have the mandate to undertake small to medium sized investments required for building climate resilience. However, most local authorities cannot effectively contribute to climate change adaptation for different reasons. There can be general lack of appropriate budget allocations leading to unfunded mandates or lack of funding for private and public-private income-generating adaptation projects. Furthermore, discussions on climate finance have been mostly limited to the national level where funding sources are mainly accessible to national programs. In some cases where funding is available at the local level, there is inability to absorb the additional cost of climate change adaptation.

Figure 3. Barriers to accessing climate finance at the subnational level

Figure 3. Barriers to accessing climate finance at the subnational level

The UN Capital Development Fund designed a global mechanism to help local authorities’ access and use climate finance effectively at the local level. The Local Climate Adaptive Living Facility (LoCAL) responds to these challenges by providing performance-based grants for climate resilience through the national intergovernmental transfer system. The Performance-Based Climate Resilience Grants (PBCRG) complement a regular financial top-up and other local revenues and channeled to strengthen national fiscal transfer systems (not parallel or ad hoc structures). It also includes minimum conditions, performance measures and an eligible investment menu aligned with the NDCs (e.g. agro-processing, agroforestry, climate smart agriculture).

Country experiences in Mozambique, Cambodia, Republic of Korea, showed that process to formulate and implement NAPs creates an enabling environment for mutually supportive planning and implementation processes for adaptation action at national and sub-national levels. The integration can be further enabled by continued strengthening of local governments’ technical capacities in matters such as planning and budgeting and financing local adaptation plans.

Synergy between UNFCCC and UNCCD

To simultaneously achieve the co-benefits of climate change adaptation and Land Degradation Neutrality

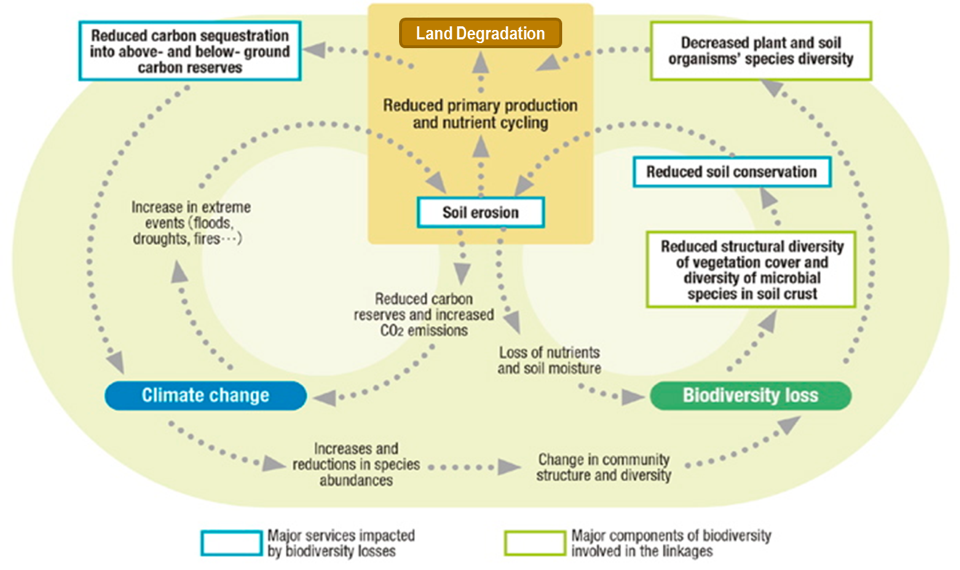

Figure 4. Land degradation reduces adaptive capacity. Source: Millennium Ecosystem Assessment 2005 Ecosystems and Human Well-being: Desertification Synthesis. Redrawn by Ministry of the Environment, Japan

Figure 4. Land degradation reduces adaptive capacity. Source: Millennium Ecosystem Assessment 2005 Ecosystems and Human Well-being: Desertification Synthesis. Redrawn by Ministry of the Environment, Japan

Seeking to address land degradation gives multiple benefits: climate change mitigation, adaptation; biodiversity conservation; food security; and sustaining livelihoods. However, the assessment captured in The Global Land Outlook released in September 2017 showed that a significant portion of the land, around 30%, of the land is degraded. Most of this degradation happened just in the last 20 years.

Around more than 1.3 billion people depend on degrading land. If the effects of recent droughts, hurricanes and forest fires are typical of the future, then the odds are greater for the poor to slide further into poverty than it to get out of poverty. And if they are able to get out of poverty, there is certainly not enough resources to sustain everyone’s lifestyle at the current levels. Resource consumption has doubled in the last 30 years. To maintain the lifestyles of the 9.6 billion people on Earth by 2050 at current level, three planets are needed to meet the required natural resources demand.

Land can accelerate many SDGs but the SDGs compete for the same land resources. The Land Degradation Neutrality (LDN) provides the framework for a balanced approach that anticipates new degradation even as we plan to reverse past degradation and one that considers tradeoffs among competing interests across the landscape. Avoiding degradation is the highest priority, followed by reducing degradation and finally reversing past degradation.

The National Adaptation Plans are in the Scientific Conceptual Framework for LDN and are directly referenced in Principle 4 of the module on Achieving Neutrality. The Scientific Conceptual Framework for LDN was endorsed by all 197 UNCCD Parties in COP 13. Thus anything in the framework which is aligned with any climate change adaptation project is a potential could be viewed as an entry point for adaptation work, This makes it highly likely ALL adaptation projects focus on land resources will contribute to achieving LDN.

Countries are embracing the LDN target: 121 countries have committed to set LDN targets so far; 83 countries have officially validated their targets; and 51 countries targets adopted by their governments.

National and sectoral M&E and learning: Assessing progress in vulnerable groups, communities and ecosystems

M&E has grown prominent in the international agenda with countries investing in the review and alignment of M&E systems in consideration of the reporting requirements under the UNFCCC, Sustainable Development Goals and the Sendai agenda, as well as in-country purposes. Emerging national adaptation M&E systems can learn from the initial experiences of building sectoral adaptation systems to address recurring challenges of lack of outcome focus; integration with development planning; capacities and resources; and synergies with monitoring of commitments under various international conventions (e.g., SDG, Sendai Framework).

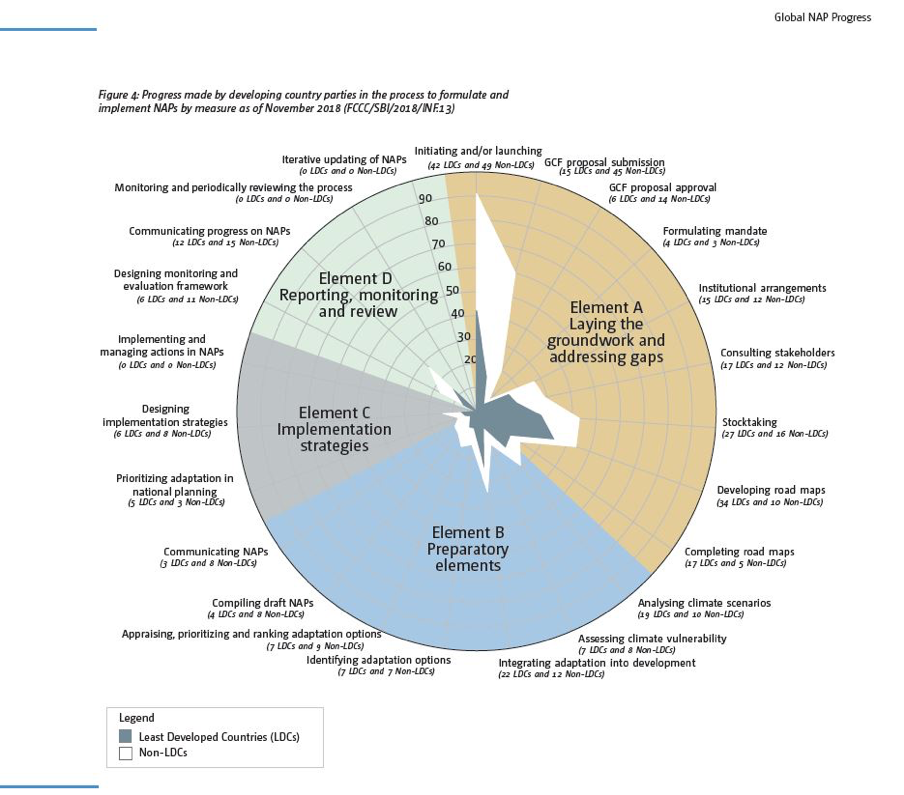

Figure 5. Progress made in the process to formulate and implement NAPs. LDC Expert Group 2018

Figure 5. Progress made in the process to formulate and implement NAPs. LDC Expert Group 2018

The development of the National Integrated M&E system (NIMES) in Kenya, to provide a reliable mechanism to monitor and evaluate implementation of government programs, faced difficulties with (1) limited information and data availability; (2) uncertainty in measurement; and (3) distinguishing between adaptation and development indicators. Lessons point to the necessity of (a) capacity building in M&E (measurement, term set, indicators mapping); (b) building baseline data; (c) sector-specific adaptation M&E; and (d) bottom-up approach in adaptation indicators mapping.

The development of monitoring and evaluation indicators for the National Adaptation Program in Agriculture (NAP-Ag) in Viet Nam was based on vulnerability assessment and suggested set of indicators in international commitments. Similar to the experience in Kenya, there is a need for capacity building at all levels. Challenges in measuring progress of adaptation was experienced in Vietnam related to the measurement of knowledge and capacity and time frame for EbA measures.

LDC Initiative for Effective Adaptation and Resilience [LIFE-AR]

The primary mandate for the LDC Initiative for Effective Adaptation and Resilience (LIFE-AR) is to develop a long term LDC vision for building resilience and adaptation towards 2050. This vision should be informed by the needs and priorities of LDCs. There is still a huge gap in funding for scaling adaptation, this is exacerbated by the lack of capacity in accessing the technical and scientific data required to access considerable amounts of funding support.

LDCs are still riddled with finding development solutions for their countries, adaptation planning adds financial fatigue to the already meagre resources they have. Coupled with inadequate awareness and understanding of available international finance the capacity to develop bankable funding proposals is still lacking in most LDCs. Where countries have managed to get proposals funded poor, M&E frameworks and indicators to track progress are usually a critical contributing factor to the failure of projects.

With LIFE-AR, LDCs are working to align their adaptation work in a systematic programmatic format as opposed to working from project to project. This ensures that learnings are captured along project implementation. By 2050 countries have vowed to have built resilient community with an enhanced adaptive capacity.

Multi-stakeholder participation and vertical integration in NAPs

The formulation and implementation of National Adaptation Plans (NAPs) involves a broad set of stakeholders and there needs to be an alignment of adaptation activities across different levels. Vertical integration is the process of creating intentional and strategic linkages between national and sub-national adaptation planning, implementation and monitoring & evaluation (M&E). It promotes the uptake of locally driven approaches which have been shown to be effective, supports adaptation planning at the subnational levels where most adaptation takes place, and promotes overall engagement of strategic partners. The NAP Global Network has developed interactive tools to assist countries mainstream vertical integration in their NAP processes.

Challenges that make vertical integration difficult at country level usually revolves around the inadequate support from legal frameworks that could regulate the involvement of different stakeholders. Most developing countries do not have the resources to carry out the necessary activities for a thorough stakeholder engagement process. Data sharing between countries and government departments is a challenge that affects the quality of participation.

Regional Technical Expert Meeting for Adaptation (TEM-A)

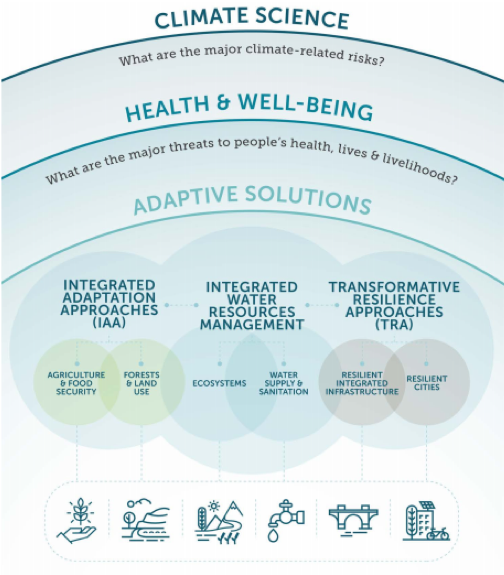

Maximizing synergies in the climate finance architecture: Lessons learned, opportunities and challenges; Private sector investment; Impact of adaptation investments for increasing resilience and reducing risk and; and sectoral roundtables on successful adaptation programmes and projects

Figure 6. Climate-resilient development will need to aim at protecting vulnerable people and communities from climate-related damages, and to maximise the benefits from climate-related opportunities, in order to boost people’s health, prosperity and livelihood opportunities. GCF’s role is to help countries prepare for this climate-resilient future. Source: Adaptation: Accelerating action towards a climate resilient future, GCF working paper No.1 (2019).

Good policy framework in some of the countries has been key in the incorporation of GCF initiatives. Pilot community-based adaptation projects in Namibia for example were successful as the locals were involved in the initial planning process of the projects. Promotion of synergies in Cambodia has been a challenge but the context of project ownership has been key in overcoming this challenge as portrayed. Preliminary understanding of the country landscape has supported some of the global agencies and networks in coordinating the adaptation activities this has resulted in gap filling and maintaining the momentum in the adaptation process.

Business model approach is core for GCF in supporting different programs has it enables the countries to develop investment plans which relatively brings together a wide array of players from different sectors under the leadership of the government. Difference in timing of the GCF deadlines and the countries’ processes has been a major impediment since countries have to wait much longer time and cycle in order to engage in the process. Some of the successful countries have attributed success in overcoming this challenge to the good coordinating institutions.

A GCF study shows that, agriculture, forestry, water as well as buildings are considered as the highest climate investment potential. However, there are still several barriers that remain to be addressed such as policy and regulatory frameworks, access to climate finance and local market, affordability and technology, knowledge and education as well as region and country related barriers.

Involvement of the private sector is key because they are the engine of economic growth in developing countries as they create jobs needed to support adaptation as well as develop the goods and services needed for societies to become more climate-resilient.